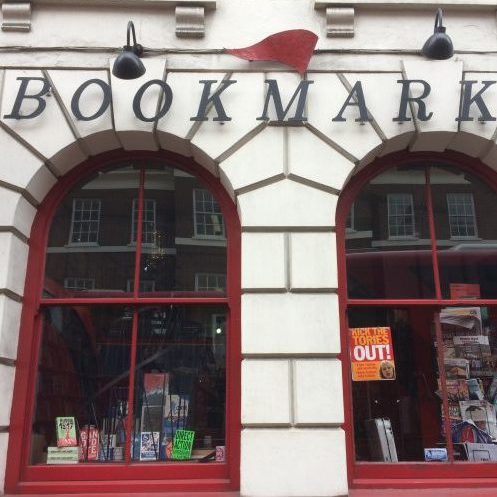

Just down the road from the Pickwick is the quaint one-unit storefront of Britain’s largest socialist bookshop. Bookmarks (I hope the pun is intended) has an extensive collection crammed into its small floor space, with a range covering the Russian Revolution, trade unionism, the Civil Rights Movement, intersectional feminism, the environment, and even children’s books for the radical early reader.

After discovering that the book on the Russian Revolution I was interested in had sold out (apparently my taste in socialist literature is pretty mainstream), I struck up a conversation with the man behind the counter. Senan has been working at Bookmarks for four years and is in charge of acquiring titles for the bookshop. We talked very briefly – it was five minutes to the end of his shift, and I didn’t want to exploit working class labor by dragging him into overtime. In those five minutes, though, I learned a good deal about Bookmarks’ history and its place in the British socialist movement. The bookshop has been around since the 1970s and is an official affiliate of the Trades Union Congress. For Senan, this means that Bookmarks has a responsibility to both education and activism – in addition to providing a repository of knowledge, the bookshop also sends representatives to conferences and demonstrations. At the same time, Bookmarks is often featured on touristy lists of Top Indie Bookstores to Visit in London! and as such draws visitors from all across the left, and even across the political spectrum. Senan signed on for the politics, and his job has delivered in so many more ways than one.

The scene doesn’t end at Bookmarks, of course; socialism gets out and about quite a bit in London. Take a walk past Soho’s restaurants and you’ll see the scruffy rooms Karl Marx made his home in the 1850s. The British Library just kicked off its Russian Revolution exhibition, Hope, Tragedy, Myths, which is hot on the heels of the Royal Academy’s feature on Russian revolutionary art that ran until last month. Heck, even the vacuous musical Half a Sixpence, skimpy on plot and character and songwriting, makes oddly literate references to the proletariat and Das Kapital. Then of course there’s the omnipresent UK welfare state, which makes provisions for the National Health Service, Jobseeker’s Allowance, and minimum wage. Socioeconomic class is clearly a big deal, and it’s interesting to see how the British situation differs from the one in America, or back home in Singapore.

The books we’re reading for Postcolonial London deal heavily in race, as one might expect from stories about immigration; what came as more of a surprise to me was how often they also raise issues of class. It’s never the story’s main attraction, but it never really goes away either. The West Indian immigrants in Sam Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners feel an affinity with the white working class, “because when you poor things does level out” (61). Andrea Levy’s Small Island depicts socialist stirrings toward the end of the Second World War and the hostile reactions from large sectors of British society, including Bernard, who equates “those men who’d cheered the Labour Party victory” (366) with “Uncle Joe Stalin’s friends” (365). In Hanif Kureishi’s The Buddha of Suburbia, our card-carrying socialist is Terry, “an active Trotskyite” (147) who “didn’t believe in social workers, left-wing politicians, radical lawyers, liberals, or gradual improvement. He wanted things to get worse rather than better. When they were at their nadir there would be a transformation” (149). Something of a caricature, in case you couldn’t tell. But ultimately these are all class-conscious characters who are obvious products of class-conscious writers, distributed among an increasingly class-conscious readership. Far from a thematic periphery, issues of class in literature reflect and translate real-world discourse that is impossible to ignore.

Class has continued to elect governments and divide societies long since the Russian Revolution – it’s as important to understand now as it ever has been. Places like Bookmarks remind me that understanding can be an accessible endeavor. Reading about class struggle in a book is by no means the same as living through it, but on the page, the political becomes a little more personal, and that’s a start. I may well revisit Britain’s largest socialist bookshop before the end of the program; maybe they’ll even have restocked my book by then.

~ Nathaniel Chew, ’19

Works Cited

Kureishi, Hanif. The Buddha of Suburbia. Faber and Faber, 2015.

Levy, Andrea. Small Island. Tinder Press, 2015.

Selvon, Sam. The Lonely Londoners. Penguin Books, 2006.