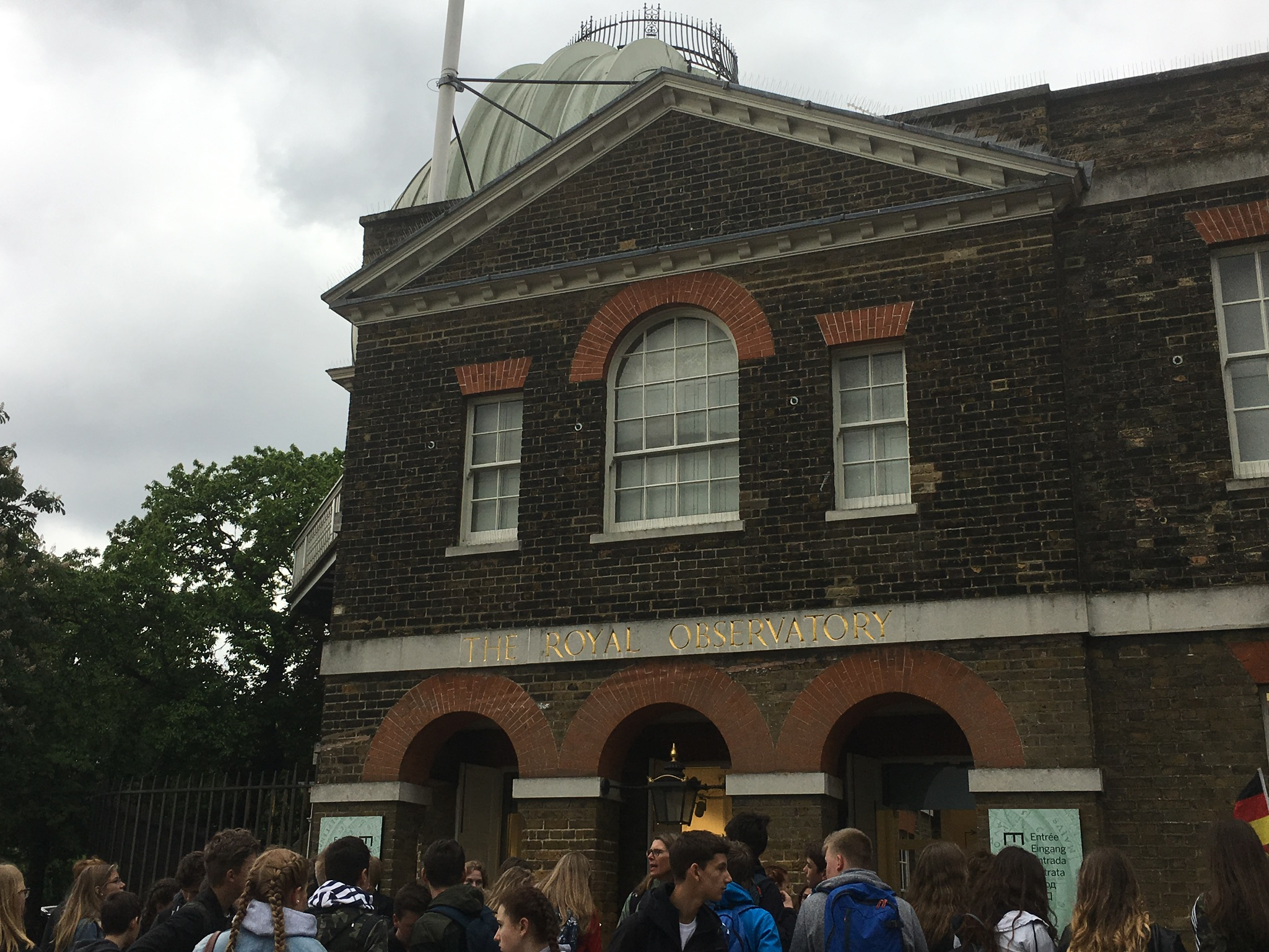

The scene is the Royal Observatory at Greenwich (pronounced GREN-itch, for some reason), UK, in 2017. A group of  well-educated American college students are gathered around a signpost indicating that they’re standing atop the Prime Meridian. “What’s the Prime Meridian for?” one asks. “It’s like, something to do with longitude and latitude?” says another. “Not exactly, it’s like…it’s about time, right, like this is the basis of Greenwich Mean Time,” says a third. “Yeah, but what makes it the Prime Meridian?” says the first student. As it turns out, that’s a good question, though perhaps not for the reason you’d expect.

well-educated American college students are gathered around a signpost indicating that they’re standing atop the Prime Meridian. “What’s the Prime Meridian for?” one asks. “It’s like, something to do with longitude and latitude?” says another. “Not exactly, it’s like…it’s about time, right, like this is the basis of Greenwich Mean Time,” says a third. “Yeah, but what makes it the Prime Meridian?” says the first student. As it turns out, that’s a good question, though perhaps not for the reason you’d expect.

First, you have to know what a meridian is. Meridians are what we call the imaginary lines of longitude, running straight from the North Pole to the South; one’s position along the meridian is given by its latitude, which is a little confusing. Meridians became significant starting as early as the 15th century, when long naval voyages promised untold wealth and power for any nations brave enough to undertake them, because of the inherent dangers of sea travel. Sailors had the skills and equipment to find their latitude fairly easily, but that was only so much help without knowing their longitude, and so the struggle to come up with a reliable way to measure one’s latitude and a universally agreed-upon map was of utmost importance. There were thousands of lives and, more importantly, loads of money at stake.

The history of how many brilliant minds colluded to solve the problem of calculating longitude at sea could be its own series of blog posts, and neither you nor I have the time for that; suffice it to say that it took until the 18th century to get a working system of calculation in place, leaving the question of where to draw the line between east and west so that everybody could be on the same map. Up through most of the 19th century, most maritime countries said that this line, the prime meridian, passed through some point in their own country, presumably for the symbolism of having their own territory being at the center of the world. As international trade grew larger and more sophisticated, so too did the need for a standardized prime meridian and with it a system of time, until 1884 when U.S. President Chester A. Arthur, whom I can safely say I’ve never heard of, called for an International Meridian Conference to settle the issue.

The history of how many brilliant minds colluded to solve the problem of calculating longitude at sea could be its own series of blog posts, and neither you nor I have the time for that; suffice it to say that it took until the 18th century to get a working system of calculation in place, leaving the question of where to draw the line between east and west so that everybody could be on the same map. Up through most of the 19th century, most maritime countries said that this line, the prime meridian, passed through some point in their own country, presumably for the symbolism of having their own territory being at the center of the world. As international trade grew larger and more sophisticated, so too did the need for a standardized prime meridian and with it a system of time, until 1884 when U.S. President Chester A. Arthur, whom I can safely say I’ve never heard of, called for an International Meridian Conference to settle the issue.

As you could probably guess, the conference ultimately sided with the meridian based on the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. Why? Simply put, there were more existing nautical charts that already aligned with the Greenwich prime meridian than with any others, so it seemed like the most sensible option. Worth note is that most of the 41 delegates at the conference represented Western countries; the U.S. and U.K. had nine between them alone, while Japan and Liberia were each the only countries from their continents to send delegates, with one each. There’s no geographical basis for the prime meridian whatsoever; it’s all arbitrary. The takeaway is that the only reason the Greenwich prime meridian is the Prime Meridian is because England had more money and power than other countries, mostly at sea, and so they got to influence how the lines were drawn. Typical, really.

Safe travels,

Matthew Pruyne

Class of ’17