In Brick Lane, I was struck by Ali’s choice to make Nazneen, as well as all the other female characters, work within the garment industry. I assumed initially it was accurate to the experience of many Bangladeshi people within England, and Ali wanted to pay respects to that with her characters. However, after visiting the fashion exhibit at the Victoria & Albert Museum, I wondered if there were other, more socially critical reasons.

Clothing is the outermost source of expression for people. Just like with anything else in society, there are rules. For example, I was taught as a kid to never mix patterns; there should be one focal, patterned piece, and then the other pieces should accentuate the features of the patterned piece. Another example would be how we dress for certain occasions; most people would not wear a tux to McDonald’s.

However, the development of these rules, and the trends that they abide by, often come from a place of privilege; there are those who can afford to wear trendy fashion and those who cannot. This then brings up the question of who gets to wear trendy clothing in the first place, and who makes it.

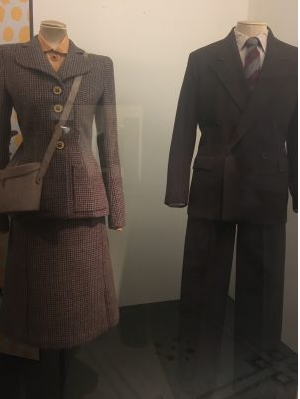

Look at these utility suits. These were designed in WWII for military personnel as a uniform. These were manufactured on a mass scale on Savile Row, instead of in the traditional bespoke fashion, so that each officer could have a professional appearance that would not bankrupt the army. This in and of itself is not a bad thing—all those people got a nice fitting, professional uniform that would last. There was camaraderie with others who shared the utility suit. However, why is that design considered “professional?” Why was the skirt the default for a woman, and a three piece suit the default for a man? Who made the suit? Does he or she have a suit? Why can’t they wear the clothing they themselves made?

These questions led me back to Nazneen as I continued wandering throughout the exhibit. At one point in the novel, a character mocks the sari as a walking cage. It stands out against the modern white, English fashion of jeans and a t-shirt. However, the crinoline itself looks more like a cage than a sari! Nazneen, choosing to wear the sari, stands out. She breaks the fashion rules of the West to fit with the fashion rules she learned in Bangladesh. However, Nazneen herself sews Western-style clothing; she makes skirts, jeans, shirts, etc., so she herself helps enforce Western clothing as normal, while simultaneously othering and re-colonizing herself. Since that is the clothing that sells, it is what must be manufactured; and as a consequence, wearing Western clothing implies that one has accepted Western culture and tastes over one’s own. If one, like Nazneen, chooses to go against that fashion, she stands out. She is the immigrant, both internally (in terms of culture and worldview) and externally (in terms of clothing).

I want to make it clear: I love fashion, and that is why I went to the exhibit in the first place. However, wandering around this exhibit, looking at all of these clothes, with the brand name listed and the sewers lost to history, it is hard to reconcile that with Nazneen’s story, only one of thousands who live life stuck between two worlds every day.

~Laudie Porter, ’18