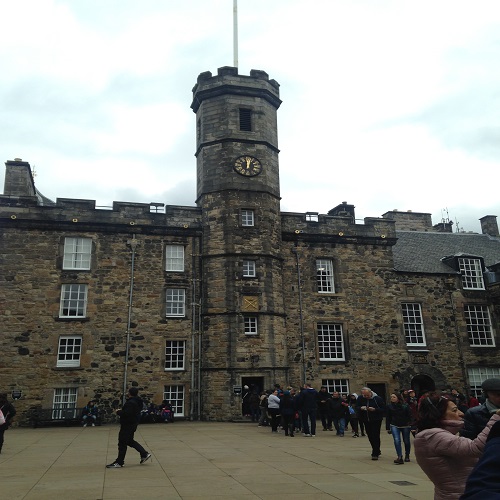

On our midterm break trip to Scotland, Laudie and I visited Edinburgh Castle. With its stone ramparts and high towers, the castle cuts a formidable figure on its hilltop perch at the edge of Old Town. The £17 tickets were not exactly cheap, but they included several museums within the castle walls. We spent roughly an hour perusing the National War Museum, which houses a collection of weapons, uniforms, and other memorabilia from several centuries of Scottish military history.

As we meandered through the displays, I was struck by the role of propaganda in shaping public perceptions of Britain’s military. I learned that many Scots who served in the British army came from the lower classes and were considered “stupid and slavish” by the general population.1 An 1805 caricature portrays new recruits as disorganized and incompetent. Later, however, I saw a rather sentimental 1882 painting by Robert Gemmel Hutchinson of Scottish soldiers saying goodbye to their families before heading to Egypt. These men “were considered romantic and dignified subjects appropriate for a prominent Scottish painter such as Hutchinson.” Clearly, public opinion of the army had altered over the course of the nineteenth century.

What happened? Understandably, a string of military victories helped boost public morale. However, the idealized soldier image was also the product of political rhetoric and military decorum, both of which relied on the imperial enterprise. As the British empire expanded, it employed lots of Scots as administrators, settlers, and soldiers in India. An 1830 portrait of General Sir Archibald Campbell makes clear the valorization of military endeavors in the colonies. Campbell led British forces to victory in their invasion of Burma, and the painting “conveys Campbell’s status as a highly successful soldier in the expansion and defense of the British empire.” With his red coat decked out in medals, he appears dignified and powerful – a far cry from the silly recruits in the earlier cartoon. A nearby display case exhibited some of these medals. One was awarded for a 1799 siege of Seringapatam, India; another commemorated British action in Burma with an engraving of a bowing elephant and an inscription, “The elephant of Ava obeys the lion of England.” Evidently, imperial success elevated a soldier’s personal standing, as well as the public image of the military as a whole.

This romanticized image contributed to recruitment efforts. A poster of a cheerful little boy holding a ball and dressed up in an army jacket proclaims, “Work and Play All Over the World.” With the British empire as a playground, propaganda painted the life of a soldier as an exciting adventure. An opportunity for glory and travel, along with job security and steady pay, must have greatly appealed to a poor Scotsman.

We’ve learned about the effects of imperialism on British colonies in our class lectures and novels, but this exhibit highlighted its influence on the Scottish people as well. In tandem with the portrayal of colonial subjects as exotic and uncivilized was the depiction of soldiers as noble and brave. Both images – subject and soldier – seemed carefully constructed to serve political aims.

This construction of the colonial soldier isn’t merely an artifact of history; the museum itself contributes to its preservation today. A jaunty portrait of Cornet James Irving, painted by a local artist during his 23 years in the Bengal Light Cavalry, puts a positive spin on colonial relations. The accompanying label reads, “[M]en like Irving spent much of their lives abroad, creating strong bonds with India and its people.” Ignoring racism and political tension, the label makes it sound like British cavalry and Indian subjects became great friends.

Things got weirder with the preserved elephant toes. Apparently, a Scottish regiment “adopted” a baby elephant in the 1830s, bringing it back to live with the troops in Edinburgh Castle. A private with a penchant for drink looked after the poor thing, bringing it around to the canteen where both would consume copious quantities of beer. After man and elephant got drunk, they would sleep it off together. The elephant died in 1840, and its toes were kept as a memento.

I found this anecdote rather troubling for two reasons. First, a quick Google search reveals that elephants have an average life span of 40 years,2 so the fact that this baby elephant died less than a decade after entering captivity suggests that neither Scotland nor alcohol were conducive to its health. Animal rights issues aside, this story also contributes to the Disneyfication of the colonial enterprise. Not only did soldiers befriend the Indians, they adopted baby elephants! How cute. Clearly, the idealization of colonialism isn’t restricted to nineteenth century propaganda alone; the museum is also responsible for maintaining this narrative.

Maybe I shouldn’t be too surprised. Edinburgh Castle brings in tourist dollars by appealing to romantic notions of Scottish history, so a nuanced critique of colonialism might be best sought elsewhere.

~Grace Johnson, ’18.

- All quotes come from the National War Museum, Edinburgh, Scotland.

- Mott, Maryann. “Wild Elephants Live Longer Than Their Zoo Counterparts.” National Geographic. National Geographic Society, 11 Dec. 2008. Web. 06 May 2017.