“The Swedenborg Society provides for the continuation of the public knowledge of the works of Emmanuel Swedenborg, the appreciation of Swedenborg’s ideas and the influence of his works on later generations. We hold that Swedenborg’s work and legacy will always remain of importance and we support work that is evidence of its continued relevance. As an institution in the service of society, and open to the public, we give home to a permanent collection of artefacts, a library, a bookroom, an exhibition space and meeting rooms. The Society offers a community to all who share these interests and, within its means, support for all those who seriously further those interests in research or interpretation.”

– Mission Statement of The Swedenborg Society (“MISSION STATEMENT”)

For us students on the program, there is one building that we have become very familiar with over the last few weeks: The Swedenborg House. It is home to our classroom, just a hop and a skip away from where we are staying at Pickwick Hall. This week during Brian Murray’s Urban Field Studies Class, we learned about Bloomsbury, an area of the London borough of Camden–our home in London. With the Swedenborg House located in Bloomsbury and being a place we go to but know so little about, I wanted to find out more about it.

To understand Swedenborg House, we must understand the society that owns the house: The Swedenborg Society. According to their website, the society was founded in 1810, with the purpose of translating and publishing the works of Emanuel Swedenborg, a Swedish scientist and philosopher (more on him later) (“About the Society”). As you can see from their mission statement above, they serve many roles—library, publisher, bookshop, and meeting space. George Prichard, a lawyer, created the society and the original meeting place was in Prichard’s house on Essex Street (about 20 minutes southeast of where the Swedenborg House is today). They were not the first group to publish and circulate the works of Emanuel Swedenborg in London, as other groups had been doing this since 1782. (“HISTORY”) But, they soon became the sole publisher of Swedenborg in the United Kingdom after their founding.

Many prominent figures were a part of the society. Among its founding members were John Flaxman, a famous artist and sculptor. Charles Augustus Tulk, another founding member, was a Member of Parliament and one of the first proprietors of University College London. One of the first translators of Swedenborg’s work for the society was Reverend John Clowes, a Manchester Anglican clergyman and Rector of St John’s Church (“HISTORY”). In 1855, the Reverend Augustus Clissold provided funds to purchase a 72-year lease, so the society was able to get its first permanent residence, located on Bloomsbury Street (“HISTORY”).

Many prominent figures were a part of the society. Among its founding members were John Flaxman, a famous artist and sculptor. Charles Augustus Tulk, another founding member, was a Member of Parliament and one of the first proprietors of University College London. One of the first translators of Swedenborg’s work for the society was Reverend John Clowes, a Manchester Anglican clergyman and Rector of St John’s Church (“HISTORY”). In 1855, the Reverend Augustus Clissold provided funds to purchase a 72-year lease, so the society was able to get its first permanent residence, located on Bloomsbury Street (“HISTORY”).

In 1925 the lease on their first residence was up, so the society moved to its current residence on Bloomsbury Way. The building is a Grade II listed building and was originally built as a residence building in 1760 (“About the Society”). WWII was hard o n the society–especially financially. But, their new residence made it through the bombings unscathed. And as we all know, the society still continues its work some 200 years later. It has worldwide membership and still elects a board of trustees each year, with its current president being Homero Aridjis, an author and former Mexican Ambassador to the Netherlands, Switzerland and UNESCO (“TRUSTEES”).

n the society–especially financially. But, their new residence made it through the bombings unscathed. And as we all know, the society still continues its work some 200 years later. It has worldwide membership and still elects a board of trustees each year, with its current president being Homero Aridjis, an author and former Mexican Ambassador to the Netherlands, Switzerland and UNESCO (“TRUSTEES”).

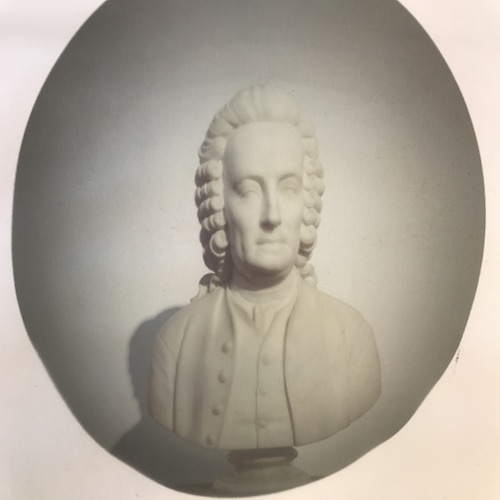

By now I’m sure you want to know: who was Emanuel Swedenborg? He was born on January 29th, 1688 in Stockholm, Sweden. From age 11 onward he was educated at the University of Uppsala, where he studied medicine, math, astronomy, natural science, Latin and Greek (“EMMANUEL SWEDENBORG”). As a young man he was known for his mechanical inventions—drawing up plans for a submarine and a glider aircraft. He held the position of Assessor of the Royal College of the Mines for thirty-one years (“EMMANUEL SWEDENBORG”). In 1719 his family was ennobled and took the name Swedenborg (his original family name was Swedberg). He also contributed to the Swedish House of Nobles, especia lly on economic, financial, and foreign affairs issues.

lly on economic, financial, and foreign affairs issues.

He had numerous accomplishments. In the field of the physical sciences he speculated about the nature of matter and anticipated cosmology as Immanuel Kant and Pierre Simon later discovered it (“EMMANUEL SWEDENBORG”). In anatomy, he discovered that lungs purify the blood, as well as accurately describing the importance of the cerebral cortex (“EMMANUEL SWEDENBORG”).

He then changed course in the 1740’s, and believed that God wanted him to interpret scripture. It was a time of introspection for him. Swedenborg published eight volumes of a book titled Arcana Caelestia (Heavenly Secrets) between 1749 and 1756. A main argument that came out of these writings was that Genesis was figurative, not literal (“EMMANUEL SWEDENBORG”). In 1758 he published his most famous work, Heaven and Hell, describing a spiritual world like our own world. He describes this world as, “one of ‘states’ of consciousness where time and space as we know them do not exist, but…where spirits eat, sleep, talk, read books, work and make love, just as humans do here, although clothed in a ‘spiritual’, not a natural, body” (“EMMANUEL SWEDENBORG”). Though he was never married, he did discuss his marital beliefs in his book, Conjugial Love, published in 1768. The book goes deeply into the topic of human sexual conduct, and its great lyricism inspired poetry of the Romantic and Victorian periods (“EMMANUEL SWEDENBORG”). He died in 1772, and shortly thereafter publishers and societies of his work began to pop up.

But, what are Emmanuel Swedenborg’s, and the Swedenborg Society’s, impact today? Upon completion of my research, I was amazed at how much of Swedenborg’s findings are taught in my classes at Carleton—without even knowing the findings are his! In my astronomy class we learned about Kant and Simon and their idea of the planets and stars forming from gases and gravity. In religion, my class debated about how Genesis should be read, and how interpretations of the Bible form the debates of religion. Even my  economics classes had Swedenborg, as he wrote a paper on the problems of inflation while he was doing work for the House of Nobles, and he correctly identified some of the dangers of inflation. His work continues to be influential—which is one of the driving forces behind why the society has been able to stay relevant for so long. They continue to sell and interpret his works—not only in the Swedenborg House, but also online. Because of their worldwide membership, they also have numerous satellite societies in other countries. But beyond this, they also continue to provide other social good to the community. You can rent out rooms in the Swedenborg House, like we do for class lectures, and they offer events for the public ranging from talks and lectures to the Swedenborg Film Festival. It is safe to say Swedenborg and the Swedenborg Society continue to have a positive global impact to this day. If you want to know more about Swedenborg or The Swedenborg Society, membership into the society, internships (looking at you Carleton students!), or their upcoming events, check out their website at www.swedenborg.org.uk.

economics classes had Swedenborg, as he wrote a paper on the problems of inflation while he was doing work for the House of Nobles, and he correctly identified some of the dangers of inflation. His work continues to be influential—which is one of the driving forces behind why the society has been able to stay relevant for so long. They continue to sell and interpret his works—not only in the Swedenborg House, but also online. Because of their worldwide membership, they also have numerous satellite societies in other countries. But beyond this, they also continue to provide other social good to the community. You can rent out rooms in the Swedenborg House, like we do for class lectures, and they offer events for the public ranging from talks and lectures to the Swedenborg Film Festival. It is safe to say Swedenborg and the Swedenborg Society continue to have a positive global impact to this day. If you want to know more about Swedenborg or The Swedenborg Society, membership into the society, internships (looking at you Carleton students!), or their upcoming events, check out their website at www.swedenborg.org.uk.

– Brandon B. Fabel ’18

Bibliography

“About the Society .” The Swedenborg Society. The Swedenborg Society , 2017. Web. Apr. 2017.

“EMANUEL SWEDENBORG.” The Swedenborg Society. The Swedenborg Society , 2017. Web. Apr. 2017.

“HISTORY.” The Swedenborg Society. The Swedenborg Society , 2017. Web. Apr. 2017.

“MISSION STATEMENT.” The Swedenborg Society. The Swedenborg Society , 2017. Web. Apr. 2017.

“TRUSTEES.” The Swedenborg Society. The Swedenborg Society , 2017. Web. Apr. 2017.