Polish Immigrants in London

Hannah Aylward, ’19 and Grace Johnson, ’18

Introduction

We have been learning about London’s immigrant populations in our Urban Field Studies and Postcolonial Literature classes; however, we did not discuss Poles, who currently represent the largest immigrant group in England. For our final project, we set out to explore Polish migration to London via the Polish Social and Cultural Association (POSK) in Hammersmith. In this post, we recount the history of Polish immigrants in the city and POSK’s establishment before describing our visit to the center and its activities today. We also touch on the future of POSK and London’s Polish population as a whole — topics that have become increasingly relevant given the recent influx of immigrants and post-Brexit tensions.

Background

Poles have a long history in the United Kingdom. Between 1891 and 1893, there were 73,000 Russian and Polish immigrants–they were counted together–who arrived in the UK (“Strangers”). In 2015, Poles overtook Indians as the largest non-British nationality in the UK, with 916,000 people counted (“Poland”). Polish immigration to England has been relatively constant, but there was a large influx during and immediately after World War II. In fact, the British government offered British citizenship to over 200,000 Polish troops who had been displaced by the war in the Polish Resettlement Act of 1947 (“Polish Resettlement”). Many civilians also fled their homes during the war and came to the UK. Most recently, Poland’s 2004 incorporation into the EU has sparked another influx of immigrants seeking financial prosperity (Kusek 107).

Along with the high-profile status of Poles in England as the largest immigrant group, we chose to focus on this population because of a personal connection. Hannah’s grandparents and mother left Poland two decades after the war, but they came to the United States, not the United Kingdom. The rest of her family is still in Poland, including Lech Walesa, the famous leader of the Solidarity movement against communism in Poland. We were able to use her mother as a translator for some of the documents we only had access to in Polish, which was a big benefit to our project.

Choosing the Polish Social and Cultural Association (POSK) for our project wasn’t difficult; a quick Google search about Polish immigrants in London shows that it is the central hub of Polish culture in England. It is authentically Polish: their website’s default language is Polish, the interior of their building is covered in Polish flyers and posters, and the staff speaks Polish automatically and English reluctantly.

The Polish Social and Cultural Association was formed in 1964. Its goal was to consolidate and strengthen the Polish community in London, and to provide a space for Polish culture to survive and be cultivated in England (“Yearly Review”). It is located in Hammersmith, where a sizeable Polish community lived and still lives (“London’s Immigrant Districts”).

History of POSK

Polish immigration in London hinges on the formation of POSK. According to Pawel Chojnacki, “the whole social history of Poles in London . . . seems to be divided into two periods: before POSK and after its establishment” (268). Prior to POSK, Polish communities developed in various parts of the city. In the 1950s, three community organizations were established in London’s western, southern, and southeastern regions (Chojnacki 3). These organizations primarily consisted of “the lower strata of emigre society” (19). Joanna Mludzinski, vice-chair of POSK, explains that first-generation immigrants “had no relations with the Polish government” and “very little contact with the home country.” Having established their roots in London, they recognized “a need to create a Poland outside of Poland” where they could “have the Polish traditions and food and culture” (“Interview”). Furthermore, they lacked a central library to house a collection of Polish materials dispersed throughout the city. Combined with the necessity of passing along Polish heritage to the next generation, this served as the catalyst for the formation of POSK, which was officially chartered on July 23, 1964. In addition to the library, POSK’s initiators built a theater, art gallery, and restaurant within the center (Chojnacki 257). At this point, West London contained the largest concentration of Poles (32 percent of all Poles in the city), and it was determined that POSK would be built in Hammersmith (260). The three previously established Polish organizations provided financial and administrative support in this endeavor, and both the West and South London centers became incorporated into POSK (3). The building first opened in 1974 and from then on marked the centralization of Polish community life in London (“Interview”).

What We Did

We conducted two interviews for this project, one informal and one formal. We first had an informal conversation with one of the librarians at the Polish library. During our visit to POSK on May 17th, 2017, we spent most of our time there. It is both a research and lending library, and it is extensive. There is a large underground archives section, almost entirely in Polish, available to anyone. The librarian told us that academics and professionals often use the library and its archives for research, but many people also come to the library to read Polish magazines and books for entertainment. The librarian provided us with multiple sources that she thought would be helpful with our project, although our options were limited by our inability to read Polish.

Our second interview took place over the phone on May 27, 2017 and was more formal. It was with Joanna Mludzinski, who was the chair of POSK’s Board of Directors for the past five years, the maximum time permitted, and is now the vice-chair.

What We Learned

We used several sources from the POSK Polish library, including yearly reviews of the center that have been published since 1964. Unfortunately, these were only available in Polish; however, we had some of the original 1964 pamphlet translated by Elizabeth Aylward. It stated, “The task of the organization is to create activities aimed at consolidating and continuing the Polish tradition” (“Yearly Review”). After speaking to the vice-chair of the organization, we determined that this is still the driving force behind POSK. This is fitting, because the 1964 pamphlet also states that “this organization cannot be changed into an organization to be used for other purposes” (“Yearly Review”). We were able to learn more about the day-to-day happenings at POSK with other sources available at the library.

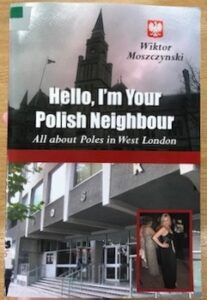

One of the sources we found at the POSK Polish library was a book by Wiktor Moszczynski, entitled Hello, I’m Your Polish Neighbor: All About Poles in West London. The cover of the book is a photo of the front of the POSK building, which shows how central POSK is to Polish life in London. The book was a collection of stories, most of which mentioned, centered around, or happened at POSK. Endless community events are hosted at POSK. People come to POSK for the restaurant, the jazz club, the art gallery, and the library, if not for one of the many events held there. These include meetings, such as a trade union recruitment meeting of Polish workers and a gathering of Polish teachers and community workers to discuss the needs of Polish students, as well as fun events like theater and dance performances (Moszczynski 17, 7). People can even register to vote at POSK during political elections (81). POSK also houses the East European Resource Center, which gives free legal and personal advice to immigrants who need assistance (“Interview”).

POSK Today

In 2016, an estimated 100,000 people visited POSK, of which 44,000 took part in various cultural events. Others came for the library, coffee bar, restaurant, and jazz club, with roughly 150 people entering the building per day. Visitor demographics vary widely, encompassing first-generation Poles who lived through the war as well as their children who were born in England (“Interview”). In a Guardian article on the importance of POSK, Annette Ormanczyk explains the center was “the most important meeting point” for young British Poles like herself in the 1980s and ‘90s. Today, Ormanczyk leads POSK’s folk dance group and describes how these dancers “deepened their understanding of the history of the local community, while having the opportunity to demonstrate their place in it.” POSK has played a key role in Mludzinski’s life as well. Her parents were involved in its establishment, and she ran the Polish Children’s Theatre for 17 years. She describes it as “close to [her] heart,” and says it is “extremely important that it keeps going, and we run it as best we can” (“Interview”).

The center is primarily run by second-generation individuals of Polish descent like Mludzinski (“Interview”). Recent literature suggests that the degree to which new arrivals engage with POSK may depend in part on socioeconomic status. Many come to London as labor migrants who maintain “close cultural and national ties to Poland.” However, the number of educated Polish “elites” in London is increasing as well (Kusek 103). Weronika Kusek notes that these elites often “view themselves as customers rather than members of the core Polish migrant community.” She explains:

“Their visits to parts of London recognized for being centers of Polish migration (for example: Acton, Hammersmith, Ealing) are occasional. When they travel to these districts, they are either focused on getting their fix of goods that they miss from Poland–poppy seed cake, seasonal items for Christmas or Easter–or on accessing services which they perceive as having superior quality to those offered by local, British counterparts (car mechanic, hairstylist, etc.)” (110).

Polish sites such as POSK are visited alongside other places that mark the emigres’ “international elite” status, such as “golf courses, tennis clubs, luxury malls, or an equestrian club” (111). Whether the centrality of POSK in the lives of new Polish arrivals will be usurped by other activities remains to be seen.

Conclusion

POSK has played a formative role in the history of Polish migration to London. Despite the diverse range of venues and events within the center, its overarching commitment to the preservation of Polish culture remains strong. To maintain POSK for future generations, the organization has become financially self-sufficient by renting out office space and adjacent property. It is planning to build additional flats nearby, although the center itself will remain as it is. POSK has recently been in the news because it was the target of xenophobic graffiti shortly after the Brexit vote. Since then, many people in the Polish community have been uncertain about their position in the UK, despite the fact that many Londoners brought flowers and cards to the center after the incident (Taylor). Mludzinski said that POSK’s legal and personal advice center has seen a growth in the number of people visiting it, and many are questioning the future of the Polish community in London.

Works Cited

“About Us.” POSK. POSK London, n.d. Web. 22 May 2017.

Chojnacki, Pawel. “The Making of Polish London Through Everyday Life, 1956-1976.” Thesis. University College London, 2008. Print.

“Interview with Joanna Mludzinski.” Telephone interview. 27 May 2017.

Kusek, Weronika A. “Transnational Identities and Immigrant Spaces of Polish Professionals in London, UK.” Journal of Cultural Geography (2015): 1-13. Web.

“London’s immigrant districts.” The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group, 16 Nov. 2012. Web. 24 May 2017.

Moszczynski, Wiktor. Hello, I’m Your Polish Neighbor: All about Poles in West London. Central Milton Keynes: AuthorHouse, 2010. Print.

“Poland Overtakes India as Country of Origin, UK Migration Statistics Show.” BBC News. BBC, 25 Aug. 2016. Web. 22 May 2017.

“Poles are biggest non-UK born population: Indians overtaken as EU nationals top 3 million.” Express. Express Newspapers, 25 Aug. 2016. Web. 27 May 2017.

“Polish Resettlement Act 1947.” Legislation.Gov.UK. Statute Law Database, 01 July 1976. Web. 27 May 2017.

“Strangers Within Our Gates.” Chambers’s journal of popular literature, science and arts, Jan. 1854- Nov. 1897; London 12.596 (Jun 1, 1895): 344-347.

Taylor, Adam. “Britain’s 850,000 Polish Citizens Face Backlash after Brexit Vote.” The Washington Post. WP Company, 28 June 2016. Web. 22 May 2017.

Yearly Review. London: POSK, 1964. Print.